From being dubbed Asia’s latest strongman, the Philippines’ new President Duterte has ensnared the imagination of the foreign press in the three months he has been the leader of this mostly Catholic nation with his deadly and unrelenting antidrug war.

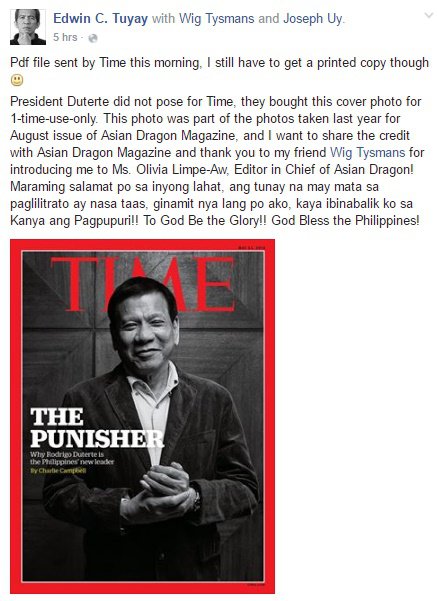

Often described as “foul-mouthed” and the “Filipino Donald Trump” for his acerbic tongue, the man who once graced the cover of Time magazine as “The Punisher” has found fresh infamy among foreign reporters who have descended on Manila to cover the daily bloodletting of suspected drug pushers and users found lifeless in its dimly-lit and grime covered streets.

At present, the police data keepers put the toll at over 3,600 dead, more than half of whom labelled as “deaths under investigation”—a euphemism for those killed by unknown vigilantes since Mr. Duterte assumed power in July.

The rest were killed in violent police encounters, their bodies typically found beside an old .38 caliber pistol. At least two—a father and son—were killed inside a police station where the cops said they had struggled and tried to fight it out.

The President has officially denied endorsing the killings, but in visits to police and military camps around the country he has publicly told law enforcers he would legally back them up if they killed suspects who threatened them harm. He has also raffled off Glock pistols, while at the same time publicly reading lists of supposed drug dealers.

“It is never wrong for a President and the police and the military to protect its citizens. It is self-preservation,” the President told policemen in a visit to the south last week, and ordered them to “go out and hunt” the drug dealers.

“I will protect you. I will not allow a single policeman doing his duty go into prison,” he stressed.

The war on drugs, he said, was not an “ordinary fight,” citing the extraordinary names in watchlists submitted to him by various law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

The list has included names of judges, public officials, police and military officers. Some of those on the list he has publicly shamed, but he has also apologized for at least two officials erroneously named, a potentially deadly mistake.

Of late, he has accused one senator, Leila de Lima, of allegedly funding her candidacy to win, in what he claimed was a clear case that “narcopolitics” has invaded the country.

De Lima has denied the accusations and said it was part of a well-crafted ploy to discredit her for fielding a self-confessed killer who testified at a Senate probe that Mr. Duterte formed the Davao Death Squad to carry out killings when he was still mayor of southern Davao City.

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Free Legal Assistance Group said they filed a request for data from the police, the interior and justice departments regarding the government’s antidrug war in early August. But more than 40 days later it has yet to receive an answer despite Mr. Duterte’s pledge of transparency.

Foreign media outfits like The Guardian and The New York Times, on the other hand, published lengthy reports on the extrajudicial killings, flying in journalists to provide gripping accounts and stories of the families and relatives of those unfortunate enough to be at the wrong end of the gun barrel.

The Guardian quoted an unnamed police officer who claimed to be a part of a secret squad that determined which criminals were to be targeted. He said he was part of 10 newly formed special operations teams, each with 16 members engaged in choosing who to kill. The BBC, meanwhile, has interviewed a woman assassin who claimed to work for the police.

Time magazine, Newsweek, Washington Post, The Australian and The Sydney Morning Herald have also sent reporters, who often found themselves crowding the press room of the Manila police department waiting for that two-way radio to go live with news of the day’s dead.

They were in cheek and jowl with Filipino reporters and photographers for foreign wire agencies and the nation’s dailies and tabloids.

President Duterte recently said US President Barack Obama “can go to hell” and his near-daily diatribes against the United Nations and the European Union have also become staples of foreign news. He was also forced to apologize after triggering an international uproar when he compared his drug war to the mass extermination of Jews by the German Nazi war machine.

Analysts have taken note of Mr. Duterte’s independent foreign policy, which appears to be increasingly favoring regional behemoth China and Russia, away from traditional ally the United States. They say the violent drug war could be a “smoke screen” to hide other issues such as massive poverty and unemployment.

“Perhaps Duterte’s landslide election has made his ego swell to such an extent he has grown delusional. Whatever the case, his regime’s wanton bloodlust is neither the stuff of intelligent policymaking nor good governance,” recently wrote Manjit Bhatia at the South China Morning Post. “It’s murder, pure and simple.”

Bhatia, an Australian research scholar who specializes in the economics and politics of Asia and the research director of the risk consultancy AsiaRisk, alleged Mr. Duterte was using the country’s drug problem “to mask his inability to produce policies to alleviate the poverty and joblessness that afflict many Filipinos.”

For feedback, complaints, or inquiries, contact us.

![]()