MANILA, Philippines – In the Philippines, no other abstract painter is as renowned as Alfredo Liongoren in perfecting figurative and other art forms. He also makes fearless excursions beyond art at the risk of silencing his canvases and compromising the visual genius he is known for. This way, he does not lose art and life, he says, adding he does not mind being life-sensitive and art-challenged at the same time.

In a one-month exhibit titled “Balesin in My Mind” currently on view until June 15 at the showroom of Alphaland Makati Place on Ayala Avenue Extension, Liongoren showed two different styles: figuration and semi-abstraction.

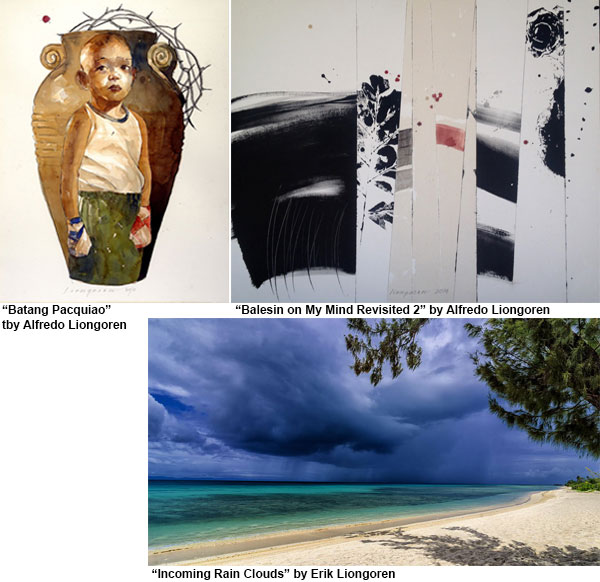

His three watercolors depict children at work, in figurative forms, a part of his “Koronang Tinik” (Crown of Thorn) series done in 2010. “Batang Pacquiao” shows a young boxer’s outstretched paw and a child’s frail image on a jar. “The series is an ode to children. Their values are affected by our moral standpoint in life. They become what we are in life,” lectures Liongoren.

Liongoren’s “Koronang Tinik“ series has an old nest. After an alliance with social realist painters who emerged in the ’70s, he focused on the oppression of the poor and learned to depict class struggle in figuration.

Also in the Alphaland exhibit are Liongoren’s seven semi-abstract art works in acrylic, meant to depict scratches on earth, extractions from nature, and lessons learned about defiled environment. Only two in the collection have pastel colors but they ache for summer and springtime, making them symbolic of buried nature or unmitigated violence against the environment. “Our land has become hostile. I keep dreaming of fertile land, budding flowers. They don’t come to the canvas yet, as I grapple life for them in my mind,” laments Liongoren.

Lifestyle Feature ( Article MRec ), pagematch: 1, sectionmatch:

“In the mid ’80s I was horrified to learn from scientists that we already lost 30 percent of our forest cover,” recalls Liongoren, who grew up seeing flocks of huge bats and playing seesaw on gigantic stalks of cassava plants in South Cotabato where his family resettled in the early ’50s. At the time, the country’s topography was already sloping as loggers rapaciously plagued the lush landscape in the south.

Looking forward after the Alphaland show, Liongoren vows, “I’ll whip up a storm. I’ll be painting to call attention to tree planting. It is an urgent thing. I want my art to serve an advocacy — to bring back the trees and make a forest. I could ally with anyone along this path.”

The exhibit, which also includes photos of his son Erik Liongoren, was earlier shown at the lobby and hallway of the posh Balesin Island Club in Polillo Island, Quezon from April 15 to May 13.

Other multi-purpose art forms

Nurturing his wall-based paintings has not stopped Liongoren from branching to other art forms for social statements.

“I am a generalist. I am into many things. I am open to alliances for the advocacies I have embraced,” he says passionately. Arguably, he has reached an unprecedented prominence by having perfected various forms of expressions, allowing him wide coverage beyond self-reference. “He cannot keep still,” says his wife Norma, head of the family-owned Liongoren Gallery on New York Street, Cubao.

In his studio in suburban Antipolp, Liongoren is busy finishing a gigantic pig-sculpture in resin. It is a stark sculpture about corruption, or a visual pun on pork barrel, the priority development assistance fund (PDAF) that lawmakers have allegedly misused for a 100 percent self-profit scheme.

“The figure is a prop for a film project titled Malayong Paglalakbay. It is like a Goliath and I will portray an old man who looks like a tired revolutionary,” he says. The film’s storyline depicts a pig that is almost hidden by a cabinet full of books — a Kafka-esque visual on bureaucracy, legalities, and technicalities that could systematically bury truth. Liongoren’s old man battles the monstrous pig with a plumb bob, which is like the slingshot of Biblical David. “It is about the eternal clash between good and evil. But for me, it is also about hope for eventual victory,” he explains. Various groups have already commissioned the film for awareness sessions before the 2016 elections.

A blue-blooded abstract artist who was attracted to socially-relevant art, Liongoren learned early that a sincere social realist artist must transcend his class and help fulfill the coming of revolution from below; and that komiks could be a perfect medium for any artist who wants his art to serve history and sociology.

“Up to now, my desire is to ‘conscientisize’ on the level of the grassroots,” Liongoren explains. How his noble aim will eventually shape his komiks in the future is yet to be seen.

Multi-diversity for Liongoren is about creativity that ripens the soul or answers questions about art’s validity. It can also eclipse abstract forms, his real forte, but it has fleshed his visual language (including the ones in his mind) with sensitivity, relevance, and time-consciousness.

Art does not vanish even when Liongoren leaves his canvases.

![]()