SAN FRANCISCO — “I went back inside the plane because it was cold. I forgot to wear the jacket which was given by my former co-worker,” recalls David Villanueva, 56, of his arrival in Los Angeles from the Philippines on January 14, 1997.

He had nothing except the clothes on his back and “the envelope from the US Embassy.”

The next day, David could not get up because of jet lag. His mother woke him up at four in the morning because she would bring him to his first job. He braved the cold and reported on his first day at 7-11 store in downtown San Diego, where he stayed for four years.

“My mom said, in America you have to get up at 4 a.m. to prepare your food and catch public transport. It’s not an easy life, but I lived it each day since then,” David says. Later, he was able to work in the government in 2001 as an office clerk through Staffing Agency Sedona and became a payroll specialist.

But that is the tail end of the meandering story of how David Villanueva, now a semi-retired Human Resources assistant of San Diego County, was able to come to America. It all had to do with his mother’s sacrifices and unrelenting will to make sure her brood would have a better life.

‘They called me impakto’

David’s mother, Socorro, went to Olongapo after World War II. She became a waitress in a bar and met Dave Belden, David’s father. When his ship left, Socorro had to bring David and his brother, Raymond, to her parents in Sorsogon so she could work.

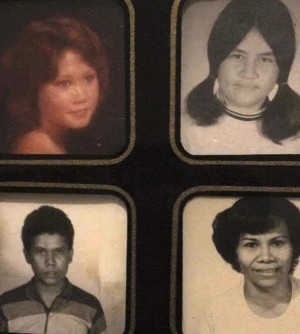

Soccoro also had two daughters. Susan, the eldest was sent for adoption as a baby. Susan lives in Hawaii. Socorro’s other daughter, Bonnie, was already 12 years old when adopted and brought to Florida. (Bonnie’s father, Mike Holmes, married Socorro but the US Embassy declared it a fake marriage.)

Socorro Villanueva in her wedding painting with Michael Holmes (left);Socorro in the United States. CONTRIBUTED

As a young boy in Sorsogon, David was called a ghost, aswang, impakto, etc. because of his looks. Afraid for his safety, his grandparents asked Socorro to take him back to Olongapo. He was already 10 years old. His schooling was supported by the Pearl S. Buck Foundation (PSBF), which supported Amerasian children. While in high school David worked as an apprentice inside the naval base for a year to help his mother. His grades suffered so he was kicked out of the scholarship. He went back to Sorsogon because he got sick, then pursued his college education in Legazpi City.

“I live with my mother’s cousin in Legazpi City. My uncle had a canteen for the employees of NFA and NBI. I worked as a server, washer and all-around helper so I could live for free,” recalls David.

David also worked as student assistant at Aquinas University. He enrolled as a medical technology student but eventually dropped out for financial reasons. His mother could not support his studies anymore because she was also struggling with her employer.

Emigration process

In 1978 Socorro went to work as house help in Hong Kong. Her employer was a Jewish-Canadian elderly woman. The employer would take her Canada and to the United States in Miami, Florida. After two years, since she still had a valid US visa, Socorro went back to Florida to visit her long-lost daughter, Bonnie. She met an American, Winfred Blaylock, who married her. She became a citizen. The couple moved to San Diego in 1985.

Socorro’s petition for David was filed in 1989. Raymond was not able to join because he was already married. David was working in Manila as housekeeper and also assigned in the maintenance of the condominium units of the Soriano family.

In 1994 a letter from the US Embassy arrived. David was given a checklist for an immigrant visa. David postponed his interview for a year because he was afraid his application would be denied.

“One day, I sought the advice of our church member. He told me that in an immigrant petition, a visa is already assigned, hence, the interview is only a formality,” David says.

With that in mind, David queued at the US Embassy. A Filipina caseworker chided him for postponing his interview when most people were so eager to come to America. The consul called him at four in the afternoon. The Embassy closed at 5 p.m.

“The consul asked me: ‘Mr. Villanueva who petitioned you’ — I answered my mom. Then he asked my mom’s last name. I said Blaylock because my mom got married twice. Anyway that’s American’s way of life; get married then divorced and married again. Then he asked again how many times my mom was married. I said, two, that I am aware of,” David chuckles.

After the interview, the consul asked David to pay for the visa; three days to pick it up and three months to use

Searching for family

David became a US citizen in 2004. Her mother passed away in 2009. He tried looking for his father, Dave, but with so many with the same names he gave up, saying that he came to America because of her mother. When he searched again in October, he found out that his biological father passed away in January.

As much as he wanted to see his sisters, David would never meet Bonnie. Bonnie was murdered by her former husband in 1985. Susan who became a flight attendant lives in Hawaii. The siblings plan to meet in the future.

“Each time I asked my mom about my siblings, she was hysterical. She would ask me if I were in the same situation without support, would I do the same. She gave them up so they could have better lives,” says David.

David’s sisters could not forgive their mother, always asking why them instead of the brothers. David never blames their mother because he knew the sacrifices she made to survive.

“Raymond is in the Philippines and never got a chance to come to America. I share everything to him so he and his family can live in comfort. But now, I am struggling again to survive here on my own,” David laments.

David still plans to retire in the Philippines at the age of 67 when he can claim his Social Security pension.

“We do not know our destiny. Just keep trusting God. Hope is our strength. Have faith that someday there is good life ahead of us. We are the only one that can make our life happy no one else,” ends David.

For feedback, complaints, or inquiries, contact us.

![]()