OAKLAND, California – Filipino food is becoming popular in the mainstream, enabled by pop-ups and chefs who are bringing their home kitchen recipes and recreating them in many venues around the nation, be they restaurants or food trucks.

Chief among its popularizers is the Filipino Food Movement. However, as the group prepares its second Savor Filipino, scheduled in Oakland on Oct. 15, it has generated controversy and criticism from some Filipino food purveyors.

Established in 201l, The Filipino Food Movement is an all-volunteer organization dedicated to increasing demand for Filipino cuisine. Founder PJ Quesada explained that it grew from a research project meant to fill “a gap between new generation of Filipinos born in the US and their culture.”

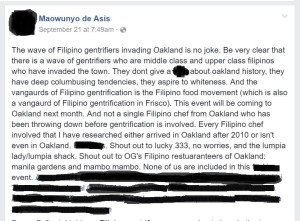

Early last week Anita de Asis, also known as Maowunyo de Asis, criticized FFM in a social media post: “The vanguard of Filipino gentrification is the Filipino Food Movement.” (full post seen in picture)

Vanguard of gentrification?

De Asis has been serving Filipino and Afro-Filipino food since 1993. She is known as the “lumpia lady because of the unique flavors of her lumpia. She is also aware of the many social issues in Oakland, including residential gentrification, which is pushing out blue-collar residents from the city.

She came to know FFM a few years ago during a Filipino event and thought its vision sounded good. “I’m always down to promote and support Filipino culture and history and businesses,” she said.

FFM promoted her on social media, but nonetheless she perceives the organization is not giving support to long-established Filipino eateries.

She said, “Oakland is a working class town. The social changes and issues of gentrification made a huge impact on the Pinoys who have been here before. Over the past years of knowing FFM, I find that they are not catering to this demographic.”

There are Filipino food businesses in Oakland that have been around for more than 20 years. Some of which are No Worries and Lucky Three Seven. Anita believes that newer Filipino restaurants are given too much attention by the FFM when they’ve only been around for a few years.

High-end audience?

“There was a huge story about FFM where every single Filipino eatery featured in the article was a high end establishment,” she complained. “Not a single mention was given to a longtime Filipino restaurant and they were toting that until that moment Filipino food was unknown to San Francisco and Oakland.”

This sentiment caused rumblings within the food community. Did FFM’s chef selection process trigger this situation? Could this be a question of communication and transparency to the community?

Asked about De Asis’ criticism, an FFM volunteer said, “We respect the opinions of food ambassadors and encourage a constructive dialogue about our differences in the hopes that we can understand each other’s perspective. We are early into our roadmap.”

There are also reports of “a pre-existing conflict” between De Asis and another chef that FFM has a relationship with.

“We featured Oakland-based chefs in 2014. We chose Oakland because we identified the ideal venue. Oakland’s vibrancy and diversity was a big factor as well,” founder PJ Quesada explained. Part of our work is to encourage dialogue and highlight various contributions to Filipino food. We have an open invitation to anyone that can contribute to the discussion.”

What to do better

Asked what could FFM do better, De Asis said, “They could do a better job in understanding the uniqueness of Oakland. Take time to learn history of Filipinos in places where they want to host their events, rather than reinvent and recreate the story of the Filipino food experience. They could start by supporting existing businesses who have been here for decades.”

She said further, “To arrive to a place you are not from and assert yourself as a leader without working with the people isn’t the right behavior. What they should have done (and still can do) is approach folks who are established leaders of Oakland’s Pilipino community and build a partnership.”

“We can see our missions aligning. It’s the execution that different,” said a representative from Chicago’s Filipino Kitchen, which partnered with FFM in “Kain na Cali” in March last year. “It seems that there is a lack of transparency and communication between FFM and the community,” the representative added.

The Filipino Kitchen representative also said that they see accusations of gentrification as a lost opportunity to build relationships between chefs. “Fostering understanding of our cuisine are goals that we share with FFM, but what metrics are they using to measure progress? They should work on identifying shared goals with all stakeholders before embarking on a project.”

Not on purpose

Stockton Chef Rob Menor, who was part of FFM’s Savor Filipino in 2014, opined:

“I don’t believe that FFM’s goal is to trigger gentrification on purpose. However, for people who don’t share their ideology I can see how they feel FFM encourages it.

Oakland has become one of the largest battlegrounds for gentrification over the past years and with the pricing and targeting of Savor Filipino an Oakland local or blue- collar Filipino food enthusiast might feel they encourage gentrification.” (Ticket prices to Savor Filipino’s ticket prices rangefrom $65 – $120.)

Menor used an analogy between Filipino Food and hip-hop music. He described the organization as social media based and have a niche with home cooks, casual foodies and who are “top 40 pop.” He said, “For them, it’s about validation from certain audiences.”

Menor explained: “Filipino food right now is what hip hop culture went through once record executives saw how commercially viable it was. We have to find balance between it all. Once you make your goal for Filipino food to go mainstream you have to be careful what you wish for.”

He said further: “That’s when people start ‘Columbusing’. That’s when people ‘discover’ what your culture has always done and cash out. I think it’s a beautiful thing to see Filipinos find identity in food. But if it’s your goal to cash out and ignore everything else then there goes problems. What’s happening now might be a sign from our ancestors to examine ourselves and what we’re doing.”

For feedback, complaints, or inquiries, contact us.

![]()