By: Emil Guillermo, September 17th, 2015 01:56 AM

The Filipino Community Hall in Delano, California looks like an old gym with a clock on the wall that looks like it’s permanently stuck in the 1940s.

That’s when the building was built, but it was in 1965 when this was the place where Filipinos made history.

Forget the champagne, pop a fresh grape in your mouth, hopefully the kind from Delano that comes with a snap. You can find them at Costco.

Fifty years ago this month, the Delano Grape Strike began.

Hey, wasn’t that the strike that turned Cesar Chavez into an American saint?

Yeah, sort of. Let’s take nothing away from the non-violent protest acumen of Chavez.

But it all came at the expense of the veteran labor strategist who made the strike happen— Larry Itliong.

You don’t have to be Filipino to make a mecca-like journey to 1457 Glenwood St. in Delano. But it wouldn’t be a bad idea.

The Grape Strike was started by Itliong (left) and the Filipinos on September 8. Itliong asked Chavez (right) to join the strike Sept. 16. Together Chavez and Larry Itliong merged their groups to form the United Farm Workers. Courtesy of Filipino American National Historical Society-Delano chapter

This is where where Itliong and members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee made history.

It’s a seminal Asian American/Filipino American story.

Like many of the strikers, my father was one of the original Filipinos to arrive in America in the ’20s. He came to San Francisco from Ilocos Norte, but he chose to stay in the city to work in restaurants and hotels.

The fields? That was hard work.

My dad didn’t escape the racism and discrimination his fellow Filipinos faced in Delano. There was plenty of that in San Francisco. And the anti-intermarriage laws fueled by angry white male nativism applied throughout the state.

But the Grape Strike gave those older workers in the fields a real way to stand up and fight back. One last time.

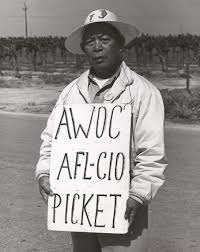

A member of Members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AFL-CIO), which went on strike September 8,1965. Composed of mostly Filipino immigrants who came the U.S. in the 20s and 30s, by 1965 many of the strikers were already in their 60s. FANHS-Delano Chapter

In a struggle that would last more than five years, the fight for fair wages and better conditions through the cry to boycott table grapes would attract iconic newsmakers like Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. to Delano.

It would also make an international labor hero of Cesar Chavez.

The media made Chavez the face of the strike, but the heart and soul of the union from the very beginning was always Asian American.

Filipinos were the vast majority of the workers who walked off the job when their demand for a $1.40 hourly wage was not met.

Their leader wasn’t Chavez.

It was the aforementioned Larry Itliong.

If I’ve told you the story before, it bears repeating. For the most part, Itliong remains forgotten and missing from the history books. If he’s included, it’s written in shorthand or dismissed as a mere footnote.

It’s the curse of most notable Filipino Americans, indicative of the inability of American society to understand exactly who and what Filipino Americans are.

Our invisibility becomes us.

But Itliong was hardly Chavez’ sidekick in one of the most significant labor movements in the last 50 years.

“My dad didn’t do it himself, but he initiated [the strike],” Johnny Itliong, Larry’s son, told me this past weekend. “How did Chavez become the founder of a union he was asked to join? That’s on him for creating that fallacy. Doesn’t mean he didn’t do any good. Just a matter of setting the record straight.”

Most K-12 history texts skip the actual beginning of the strike.

For the record, Itliong called for the strike vote in Delano’s Filipino Community Hall on Sept. 7, 1965.

The workers walked off the fields the next day, Sept. 8.

Chavez was asked to join the strike on Sept. 16.

Gil Padilla, a co-founder with Chavez of the National Farm Workers Association, remembered Chavez’ reaction. “Cesar called me early in the morning,” Padilla said at the 50th anniversary symposium in Delano. Padilla said NFWA didn’t have much membership or money and was not prepared. Initially, Chavez offered to help with pickets and leafletting.

Chavez’ NFWA also wasn’t a true union, but an association, and any talk of merging would take negotiation.

“And that’s where Larry Itliong came in,” said Padilla. “I always thought and said Larry Itliong was a very strong man. He was the one who made the decision for the negotiations between NFWA and AWOC. Larry was the one who made sure we merged together…We became a family and we merged.”

That became the true hallmark of the strike–the bringing together of new immigrants –the combined might of the growing labor force coming from Mexico, with the aging and dwindling Filipino labor force that had first arrived to America in the ’20s.

In many ways, the new United Farm Workers, the UFW, was a natural evolution of the changing work force in the fields.

“It became clear to Larry that Mexicans were the key to the success of the strike,” said Dawn Mabalon, a history professor at San Francisco State who is writing a book on Itliong. “The only way to win was with each other.”

Mabalon said that without cooperation, Filipinos would be used as scabs if Mexicans went on strike, and Mexicans would be scab labor if the Filipinos were on strike.

“The strike fused the community,” Mabalon said. And in 1965, when people were thinking about civil rights in general, the farmworkers became part of a social justice movement and made America care.

That still doesn’t explain why Chavez eclipsed Itliong so badly in terms of the historical recognition for the strike.

Paul Chavez, Cesar Chavez’ son and the president of the Cesar Chavez Foundation, admitted there were some hard feelings.

“Of course, there were,” said Chavez, who recalled his childhood around Itliong, whom he called Uncle Larry. “Who would not be offended if they felt their contributions weren’t recognized…I think there’s a need to recognize the contributions of people in Delano, Latinos and Filipinos alike.”

But how Itliong became invisible may be just a matter of timing.

“He left the UFW in 1971,” said Mabalon. “And even though it wasn’t publicly acrimonious, I think there were some hurt feelings and bitterness. He died five years after he resigned in 1977.”

It meant that when America and the media finally paid attention, they focused on Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Itliong had been dead for nearly 20 years. “He wasn’t alive to speak for himself and to be someone that people in the ’80s and ’90s could connect to and recognize in the media,” said Mabalon.

Itliong’s death in 1977 to Lou Gehrig’s disease and ALS compounded the tragedy.

“Saddest day of my life,” said Johnny Itliong, who was just 11 years old when his father died.

But the harvest may yet come for Larry Itliong.

California State Assemblyman Rob Bonta has passed a bill making the teaching of the farmworkers mandatory. Project Welga at UC Davis is among those working to provide curriculum resources on the web.

And there’s more: Gov. Jerry Brown in July declared Itliong’s birthday, Oct. 25, as Larry Itliong Day. Union City, Calif., has named a school for both Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz; in San Diego, a bridge was named for the pair. And in Stockton, a move is on to honor Itliong, a native son, by renaming a street in the heart of that city’s Little Manila. The effort is being led by Dillon Delvo, whose father was an AWOC organizer who worked with Itliong.

“It’s the responsibility of the community to do this,” said Delvo. “Larry Itliong is actually from Stockton, and hardly anyone knows that.”

But we’re coming to a real turning point for Filipinos in America, now the largest and fastest growing Asian American group in California.

Itliong’s moment is coming, and it’s about time.

I felt it in Delano.

Emil Guillermo is the winner of the 2015 of the Asian American Journalists Association’s Ahn Award for Civil Rights and Social Justice. Contact: Facebook; Twitter

Like us on Facebook

Latest

Recommended

![]()